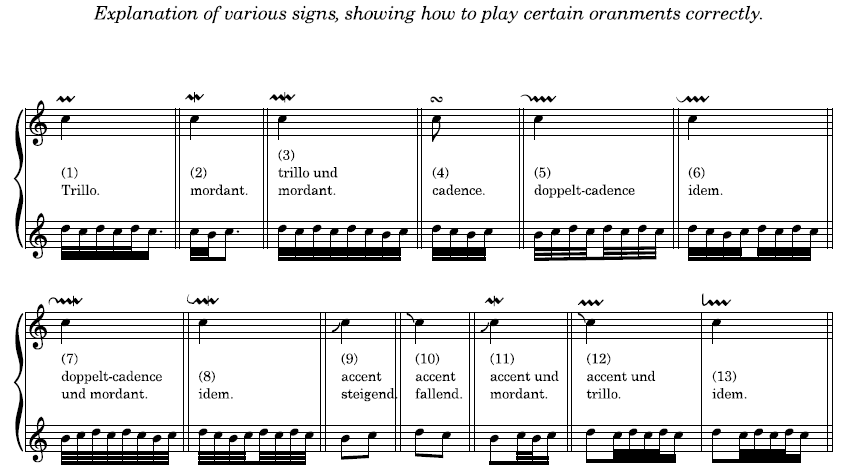

This table is given in the preface to the Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, a collection of pieces started in 1720 for J.S. Bach’s eldest son. It is the only written guide Bach gives regarding ornaments.

We have more information regarding ornamentation from Bach’s second surviving son, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. In his book Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments (first part first published 1753), he devotes an entire chapter to embellishments. Johann Joachim Quantz’s On Playing the Flute (first published 1752) is also recognized as an essential source for ornamentation practice.

A Matter of Good Taste…

There are always exceptions, and there are instances where contemporary sources are in direct contradiction to one another. This is an endless source of debate, and I would warn against trying to find absolute one-size-fits-all solutions. In the end, nearly everyone agrees that “good taste” should be the ultimate guide. So, study your sources, inform yourself through reading, listening, and discussion with others, and trust that eventually you will come to a place where you have confidence in your own voice.

A Plea for Simplicity

“Above all things, a prodigal use of embellishments must be avoided. Regard them as spices which may ruin the best dish…”—C.P.E. Bach

Purpose of Ornaments

Think of ornaments as decorations, which can serve many purposes:

- to connect notes, such as to extend a long note which might lose sound, particularly when played on an instrument such as harpsichord

- to give stress or accent to individual notes

- to mark cadences

Basics for all Baroque Ornaments

- Start the ornament ON THE BEAT

- Play the ornament DIATONICALLY (belonging to the scale), using whatever key is in force at the time (note this is very often not the same as the key signature at the beginning of the piece)

- All ornaments should be considered in the context of the principal note as well as the tempo and affect (character) of the entire piece

The following gives a brief overview of each of the 13 ornaments in Bach’s table without going into too much detail. They fall into four categories: trills, mordents, turns, and appoggiaturas.

Trills

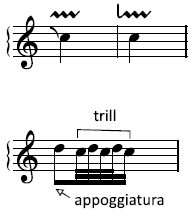

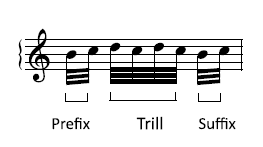

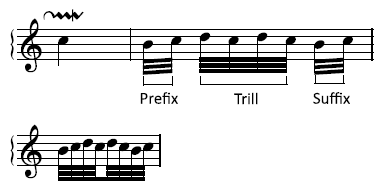

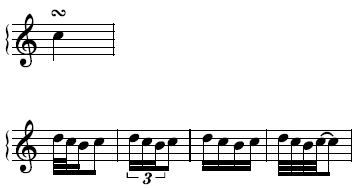

The trill is likely the most common of all ornaments. It consists of 3 possible parts: a prefix (optional), the trill itself, and a suffix (optional).

IMPORTANT: Over time, the performance practice for trills gradually changed. By the late Classical and early Romantic era (somewhere around 1800), the preference for starting a trill on the upper note changed to starting the trill on the main note. We are limiting the discussion here to J.S. Bach’s trills.

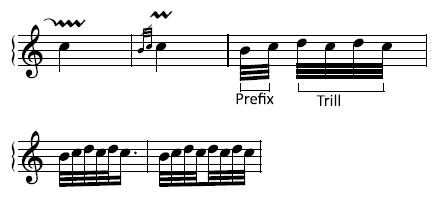

Parts of a trill:

Note: The suffix is often called a “termination” and I use these terms interchangeably

From this we have the following combinations:

- Trill

- Trill + Suffix (Termination)

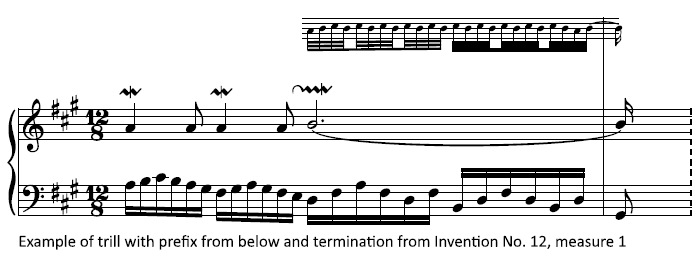

- Prefix + Trill (2 options, prefix from below or prefix from above)

- Prefix + Trill + Suffix (2 options, prefix from below or prefix from above)

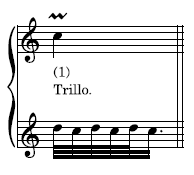

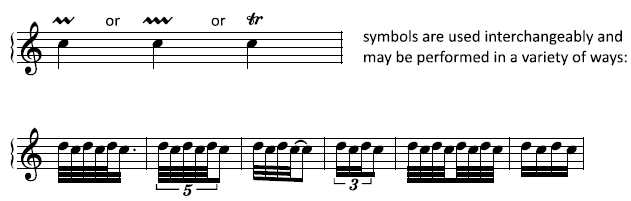

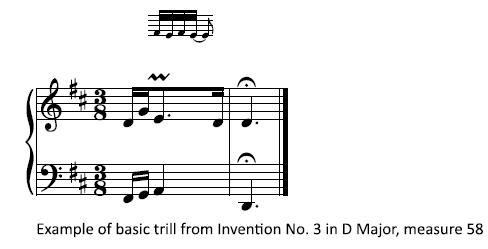

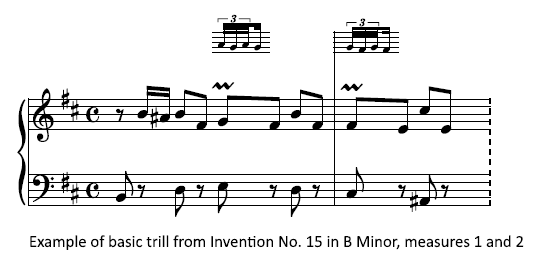

Basic Trill (Bach’s Table #1)

The trill can be short or long, depending on the length of the note and character of the piece. Below are only a few possibilities and notation does not always reflect the flexibility a trill might have. For example, in a slow expressive piece, it could be effective to start a little slower and move into a faster speed.

- Start the trill on the tone ABOVE the principal note (so if the trill is written on a C in C Major, start the trill on D)

- The length of the trill depends on the length of the note. The longer the note, the longer the trill (so a trill over a half note will have more repercussions than a trill on a quarter note)

- There is a minimum of 2 repercussions to be classified as a trill

- The trill ends on the principal note

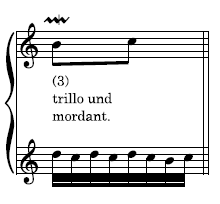

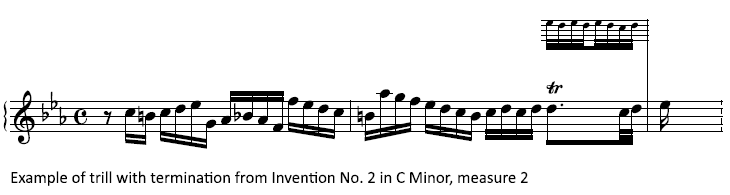

Trill with termination (Bach’s Table #3)

Other terms: Trill with Suffix, Trill with Closing Notes, Trill with Nachschlag

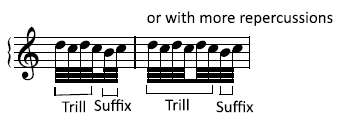

- There is a minimum of 2 shakes (4 notes) PLUS a 2-note termination

- These trills are usually somewhat longer, with the principal note being a longer duration or at a slower tempo

- Sometimes, but not always, Bach notates the termination as in the following example:

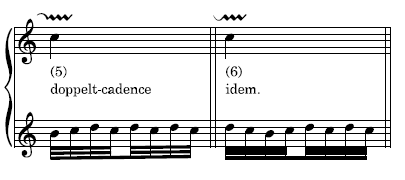

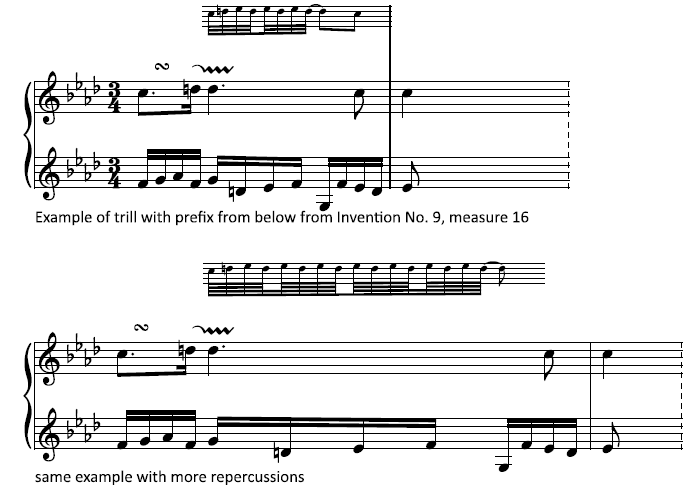

Trill + Prefix from Below (Bach’s Table #5)

Trill + Prefix from Above (Bach’s Table #6)

from below:

from above:

Trill + Prefix from Below:

with fewer repercussions (slower trill):

with more repercussions (faster trill):

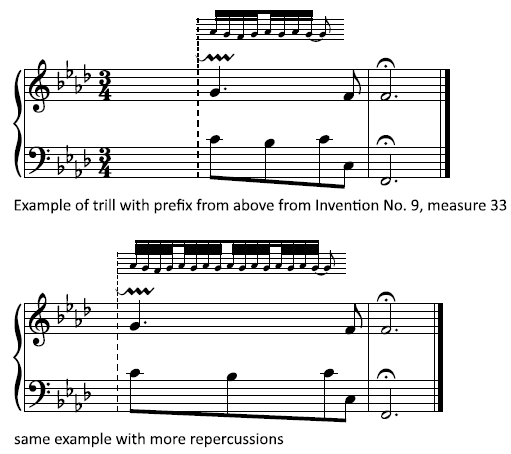

Trill + Prefix from Above:

with fewer repercussions (slower trill):

with more repercussions (faster trill):

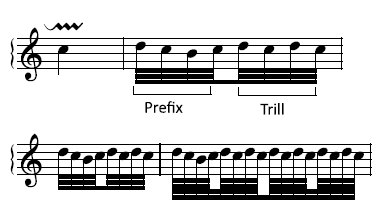

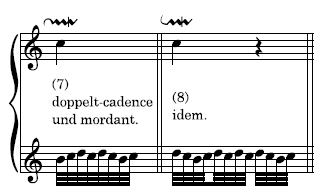

Trill + Prefix from Below + Termination (Bach’s Table #7)

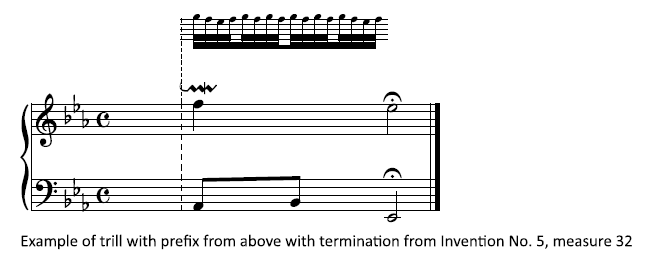

Trill + Prefix from Above + Termination (Bach’s Table #8)

from below:

from above:

Trill + Prefix from Below + Termination:

Trill + Prefix from Above + Termination:

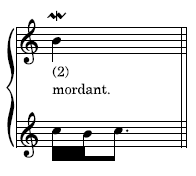

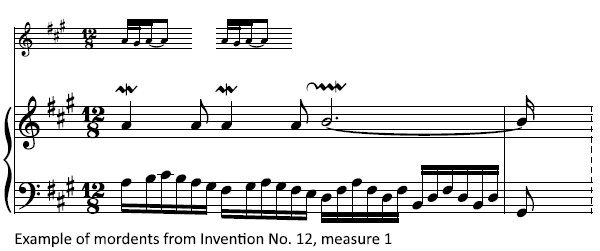

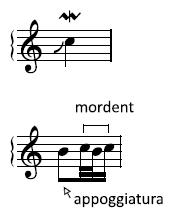

Mordent (Bach’s Table #2)

The mordent (from the Latin mordere, “to bite”), is not complicated. It is simply a quick step down and back up to the principal note. Very often it is used to make notes more brilliant, as in the example from the A Major Invention given below.

- Start with the principal note

- Move quickly down and back up

- This ornament is played quickly, and note that all 3 notation examples above sound basically the same

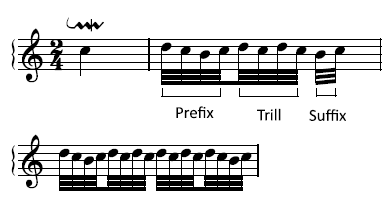

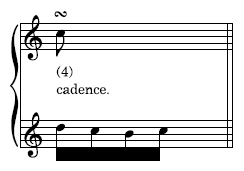

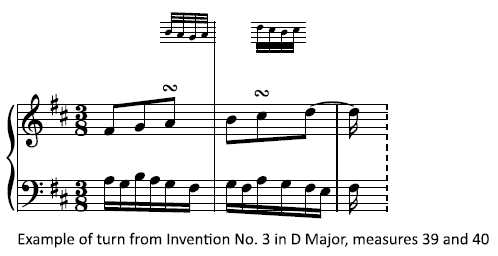

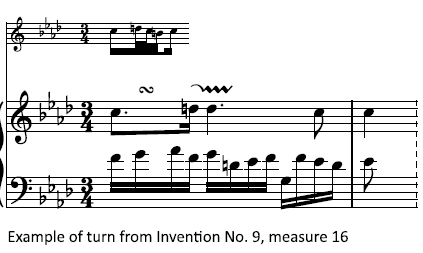

Turn (Bach’s Table #4)

The turn is often found in cadences along with a trill, but also appears in many other passages. It expands the principal note by adding a bit of movement and dissonance to the passage.

- The turn has 4 notes and uses the same formula that “turns” around the principal note:

- (1) start on the note above the principal

- (2) next play the principal

- (3) play the note below the principal

- (4) move back and end with the principal

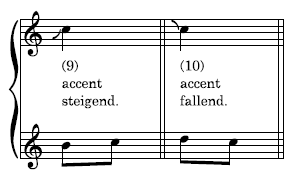

Appoggiaturas (Bach’s Table #9 and #10)

The appoggiatura (from the Italian appoggiare, “to lean,” is a note that creates tension by temporarily displacing the principal note by about half its value as it resolves into it. Bach used hooks to notate this, but that notation is no longer used.

Ascending Appoggiatura (Bach’s Table #9)

Descending Appoggiatura (Bach’s Table #10)

There should be a slight emphasis on the appoggiatura note (“lean” into that note, resolving to the principal)

C.P.E. Bach and J.J. Quantz both give the following guidelines for appoggiatura performance:

- Play the appoggiatura ON THE BEAT

- The appoggiatura takes one half of the value from the principal note

- If the principal note is dotted, then the appoggiatura takes two-thirds the value of the principal

Composers including C.P.E. Bach began to notate more specific time values of the appoggiaturas. J.S. Bach did not give any indications on this, so I personally consider there to be a good deal of flexibility and would not advise counting out exactly one-half or two-thirds.

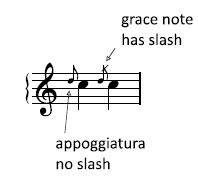

PITFALL: The appoggiatura is often confused with the grace note, which is notated with a slash on the stem and is played quickly before the beat. The grace note DOES NOT EXIST in Bach’s ornamentation world and is WRONG. There are many outdated editions in the public domain where they appear, so beware!

Appoggiatura Combinations

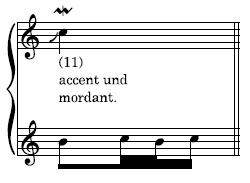

Appoggiatura + Mordent (Bach’s Table #11)

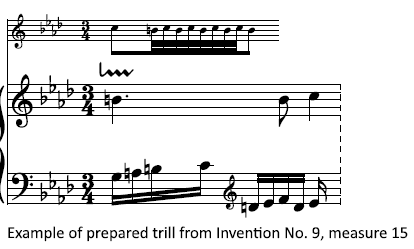

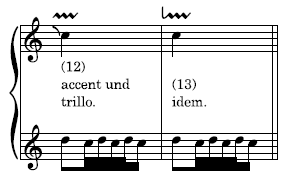

Appoggiatura + Trill (Bach’s Table #12 and #13)

- Bach shows two different ways to accomplish the same ornament in #12 and #13

- This is sometimes also called the Prepared Trill