C.P.E. Bach: Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen

(Part One 1753, Berlin)

(Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments)

I am always interested in original sources, and this is one of the best for keyboard players. C.P.E. would have formed many of his ideas from his father, the great J.S. Bach. At the same time, he was very much part of the next generation and was well known and respected on his own merits. It is well worth the effort to study the text either in the original German or the English translation. Having made my way through both, it takes time to wade through the antiquated writing style and sort out the musical examples. The following study guide is intended to make the text more accessible by providing a summary of each paragraph along with audio clips of the musical examples.

Study Guide: Summary and Examples

Chapter Two, Embellishments: The Appoggiatura

1) Appoggiaturas are among the most basic and essential ornaments. All syncopations and dissonances can be traced back to them. Appoggiaturas:

- Enhance harmony and melody

- Improve a melody by joining notes smoothly together

- Shorten long notes when needed

- Lengthen notes by repeating a preceding note

- Modify chords that would otherwise be too simple without them

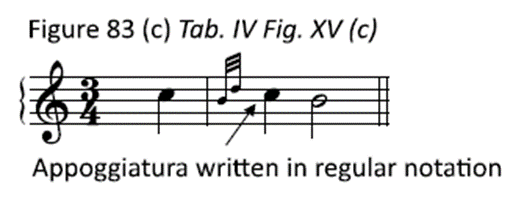

2) Appoggiaturas may be notated:

- In regular notation, giving a specific note value (these do not look like ornaments unless you are searching for them, such as looking for non-harmonic tones in theory class)

- In small notation, placed before the primary note. In this case, the primary note looks to have its full value, but in performance will lose some of its length since the appoggiatura is played ON THE BEAT

3) Appoggiaturas may be ASCENDING or DESCENDING. This section will focus on appoggiaturas written as small notes preceding the principle note, with a few comments about appoggiaturas in regular notation at the end.

4) In performance, some appoggiaturas vary in length (i.e. the variable appoggiatura), others are always played quickly (i.e. the short appoggiatura).

5) Prior to approximately the 1750’s, appoggiaturas were only written as 8th notes, and they were always played about the same way (appoggiatura played on the beat with half the value of the principal note, or 2/3 the value if dotted.) By c. 1750 composers began to notate the true note value, reflecting the greater variety of performance practice that was developing at that time.

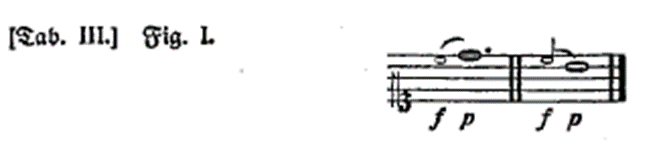

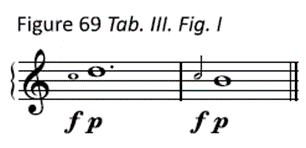

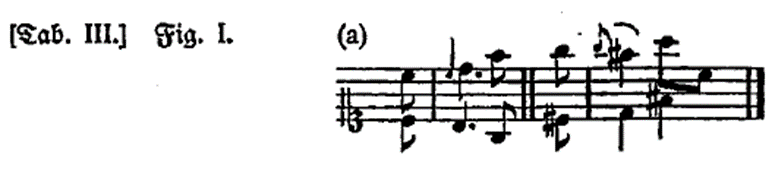

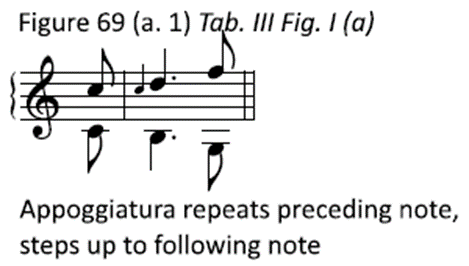

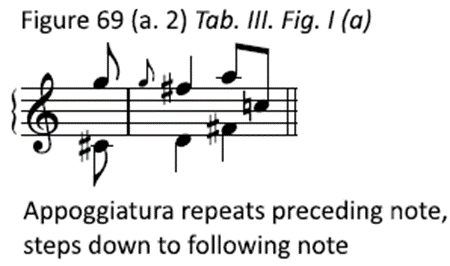

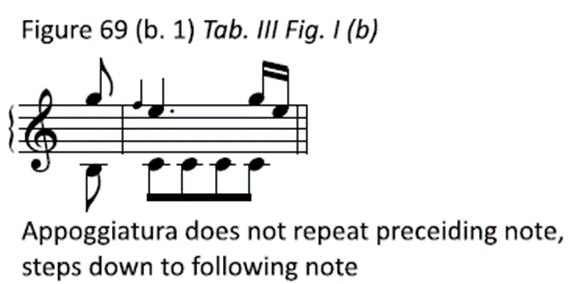

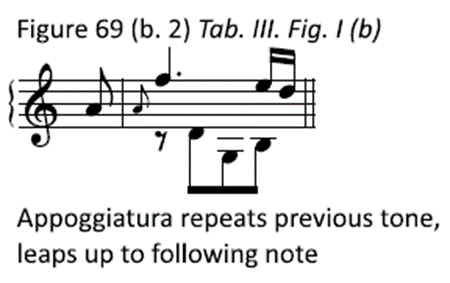

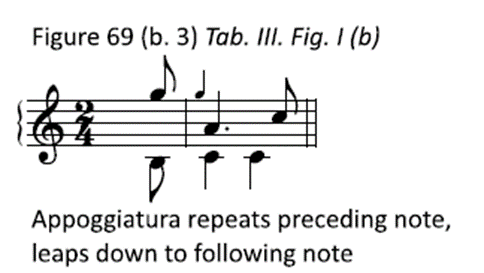

6) The following examples show typical uses of appoggiaturas (note that appoggiaturas are written in the true length to be played):

- The appoggiatura may REPEAT PRECEDING NOTE

- Other times the appoggiatura DOES NOT repeat the preceding note

- Following note may be a STEP above or below

- Following note may be a LEAP above or below

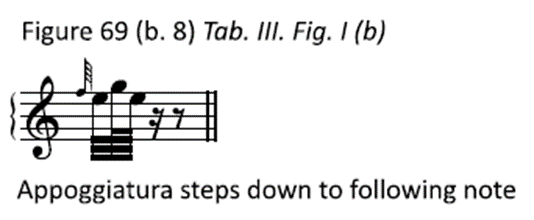

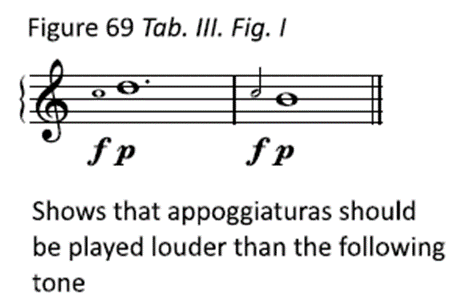

7) Performance practice:

- The appoggiatura creates tension and resolution

- The appoggiatura note is played louder (creating the tension), including louder than any other ornamentation on the resolution note

- Connect the appoggiatura (play LEGATO) to the principal note if a slur is shown or not

8) The appoggiatura is one of the few ornaments that is usually notated, since it (along with the trill) is universally known. Nevertheless, more discussion of their use is in order.

9) More examples

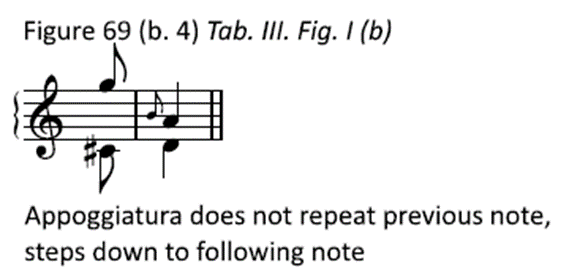

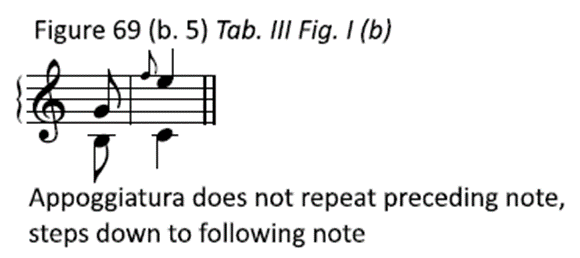

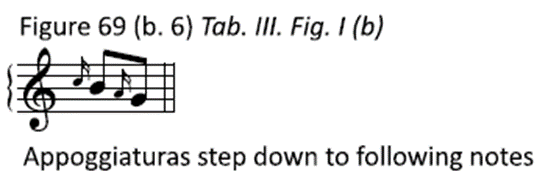

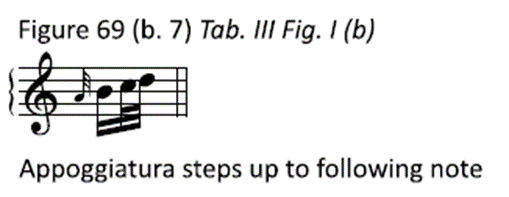

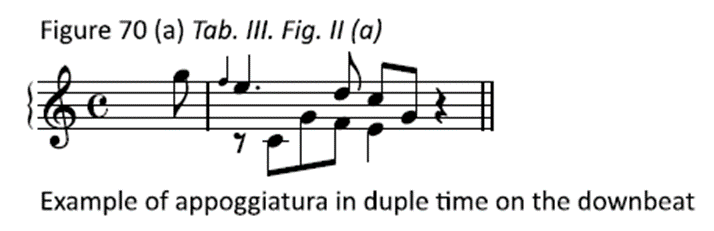

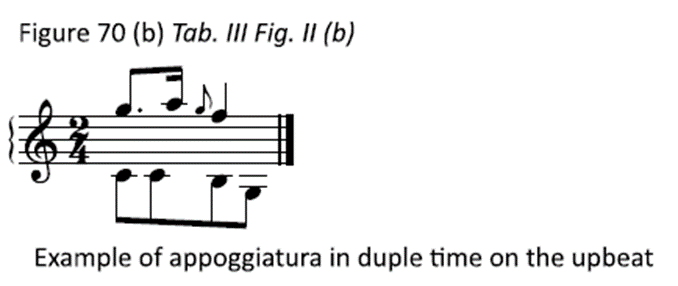

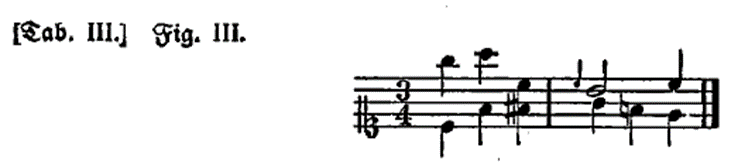

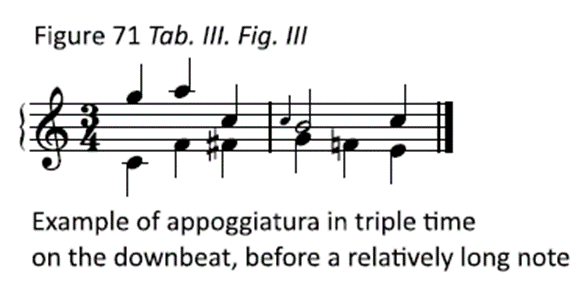

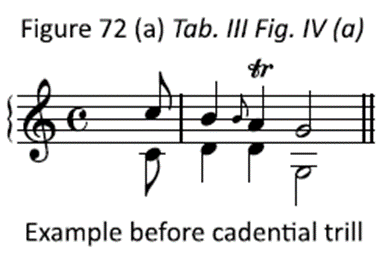

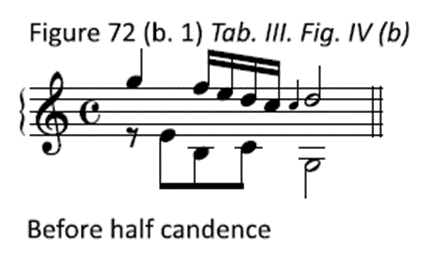

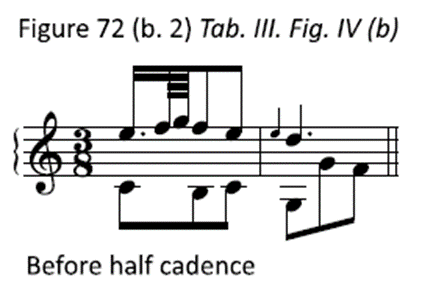

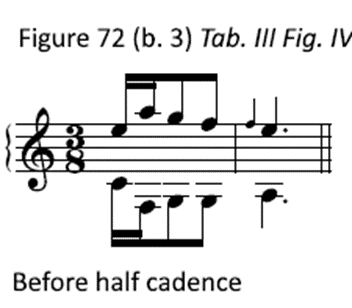

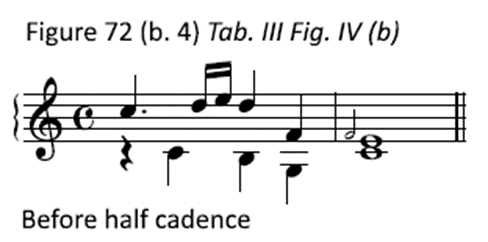

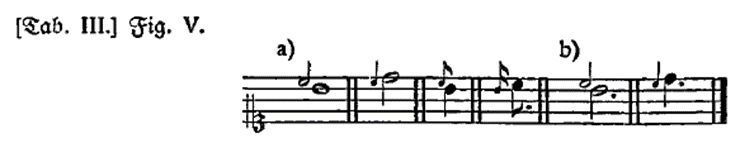

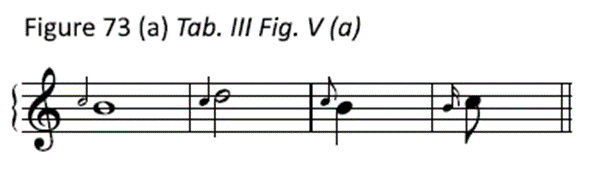

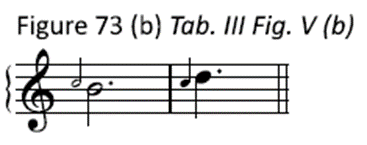

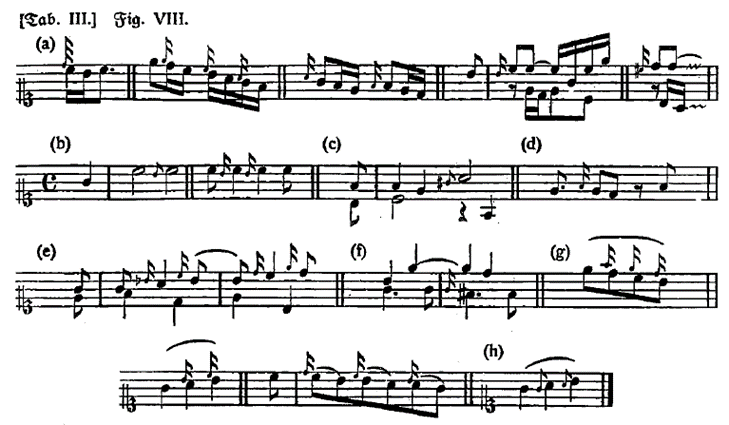

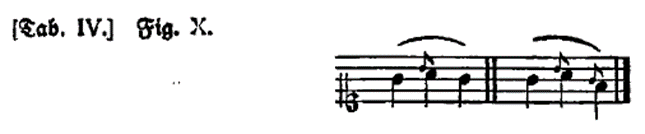

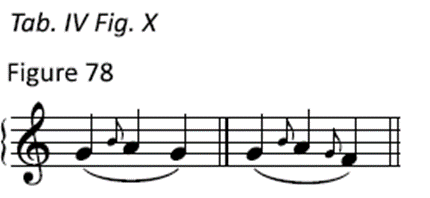

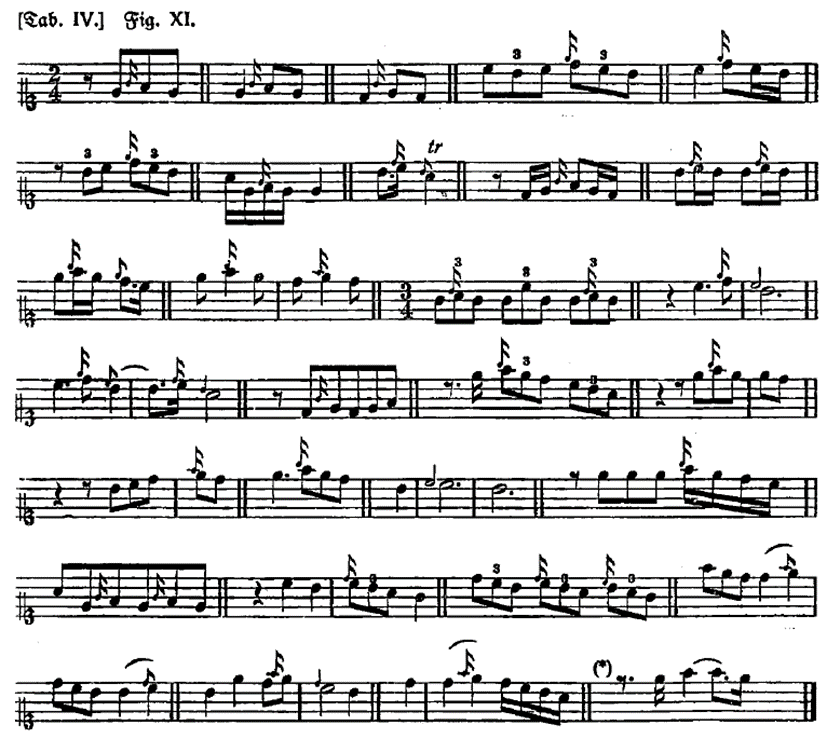

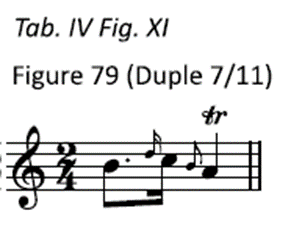

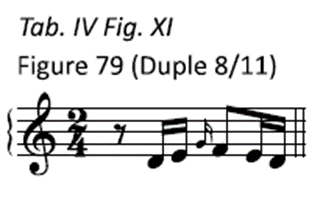

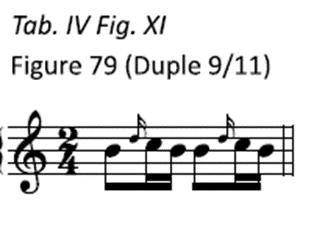

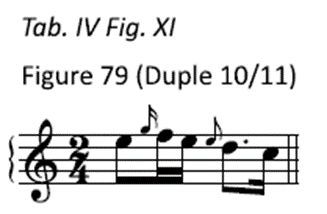

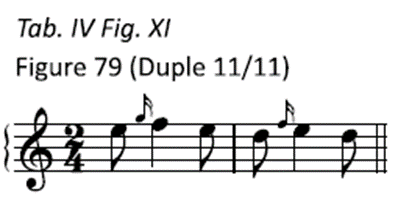

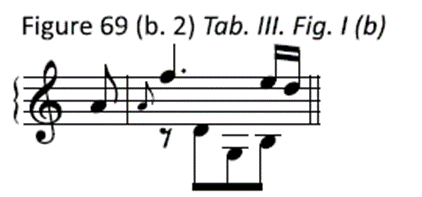

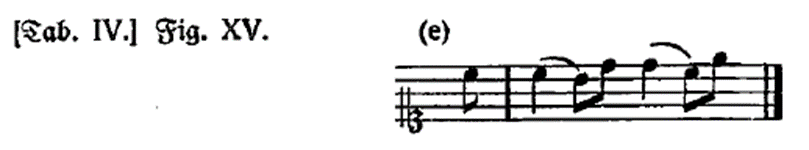

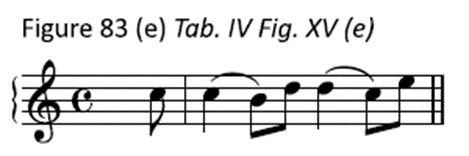

- in DUPLE time, the appoggiatura appears frequently EITHER on the downbeat (a) OR upbeat (b)

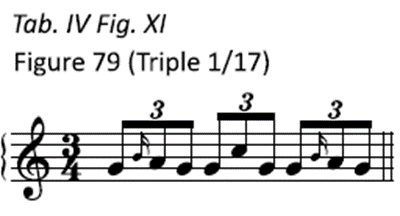

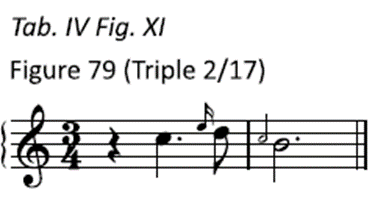

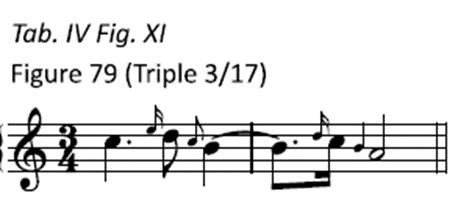

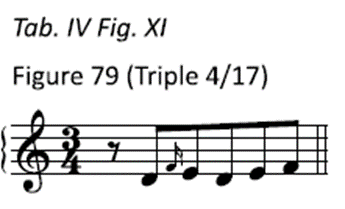

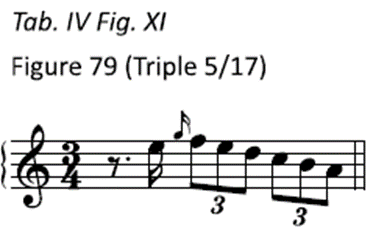

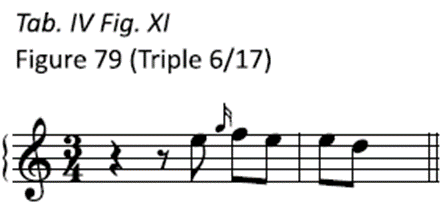

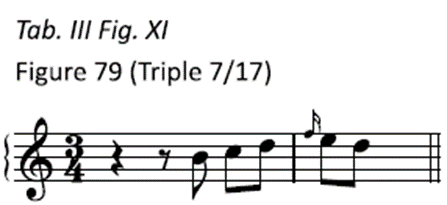

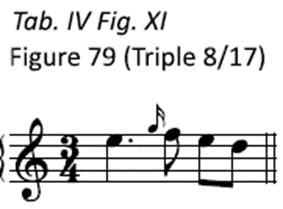

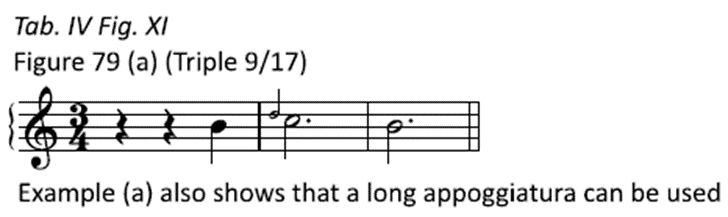

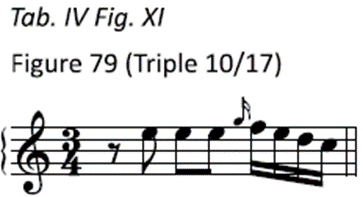

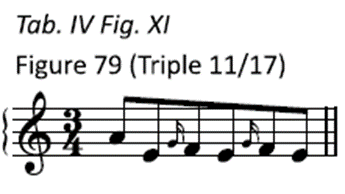

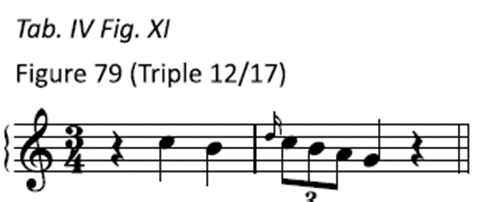

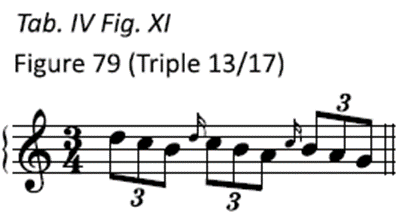

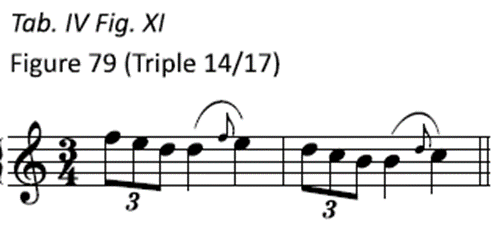

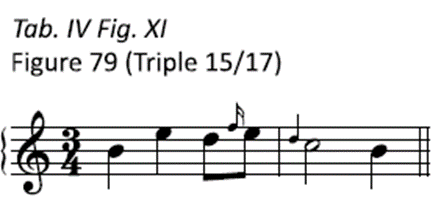

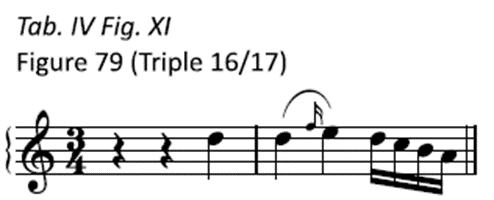

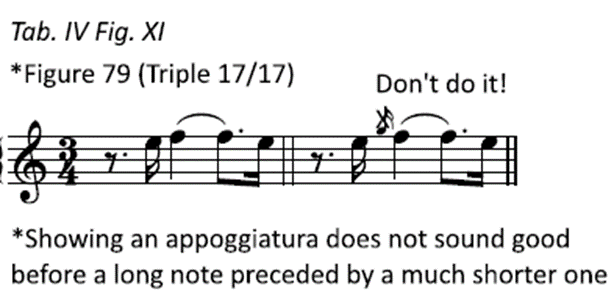

- In TRIPLE time, the appoggiatura appears ONLY on the DOWNBEAT, and always before a relatively long note

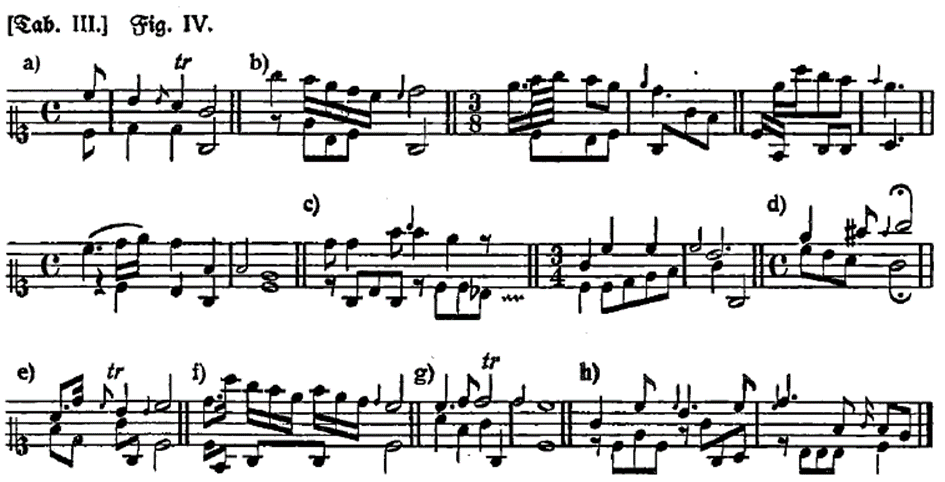

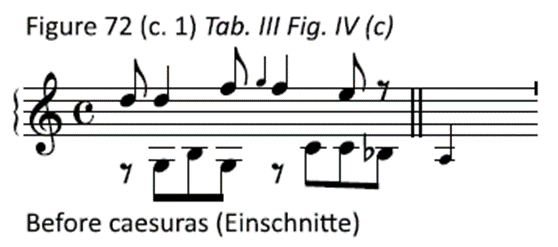

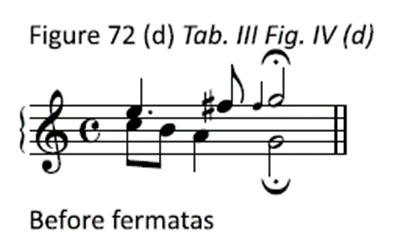

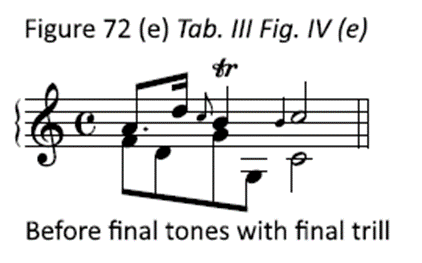

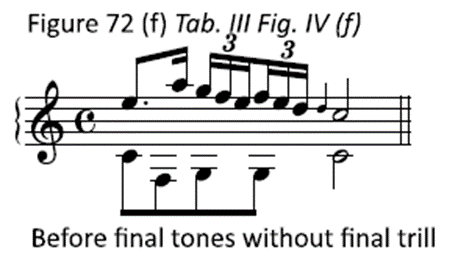

MORE EXAMPLES OF USES

- Before cadential trills

- Before half cadences

- Caesuras (Einschnitte)

- Fermatas

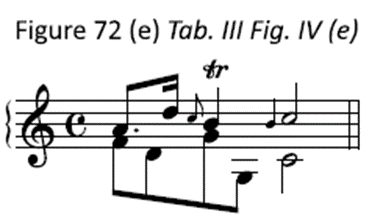

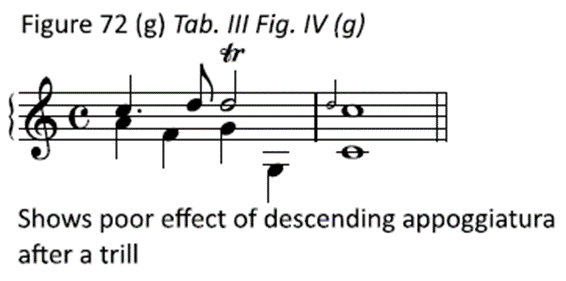

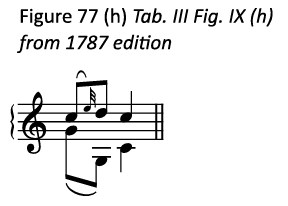

- Final tones with (e) or without (f) a final trill

- Ascending appoggiatura after a trill is better (ex. e) than descending (ex. g)

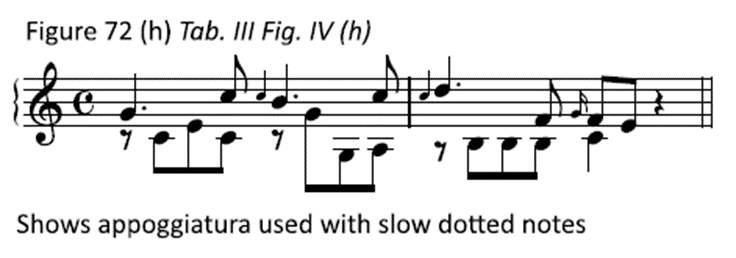

- The appoggiatura can also appear with slow dotted notes (ex. h). If these notes have trills, the tempo must be appropriate.

10) Unless it repeats the preceding tone, the ascending appoggiatura is difficult to use. The descending kind can be found in many contexts.

11) The usual rules for appoggiaturas:

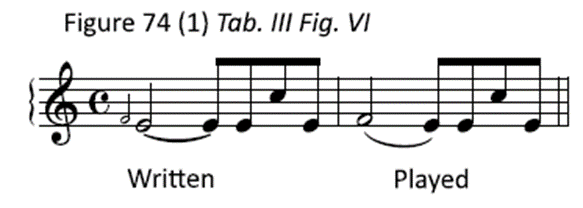

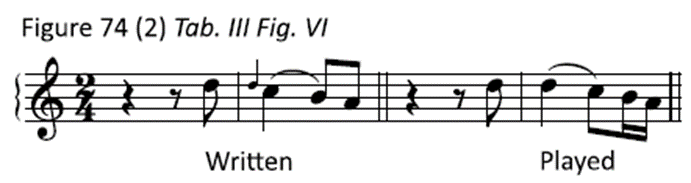

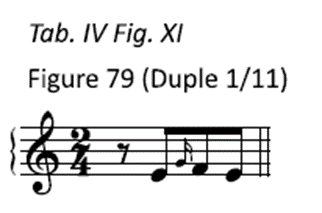

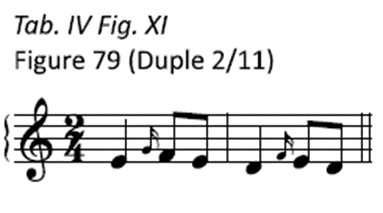

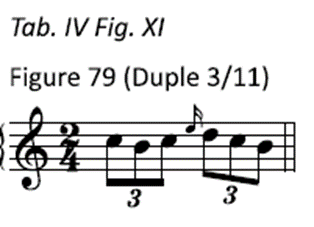

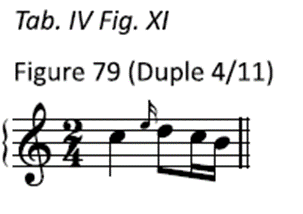

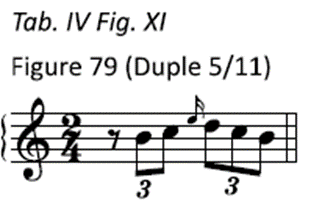

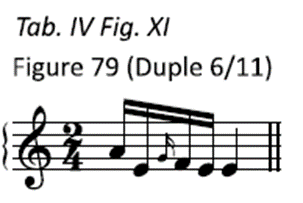

- In duple time (where the beat divides into two parts), the appoggiatura takes one-half of the following note’s time

- When the beats divide into 3 parts (dotted notes), the appoggiatura takes 2/3 of the following note’s time

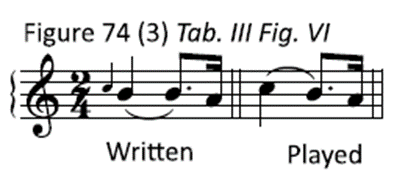

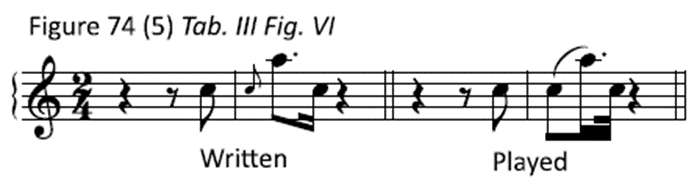

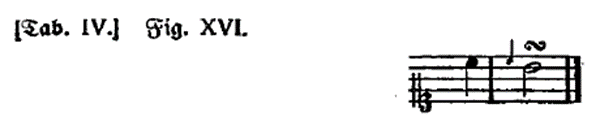

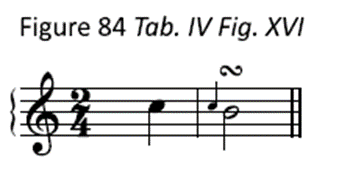

- Study the examples in Figure 74 (Tab. III. Fig. VI)as well, and anything that is an exception to the usual performance rules should be written in regular notation to avoid misinterpretations.

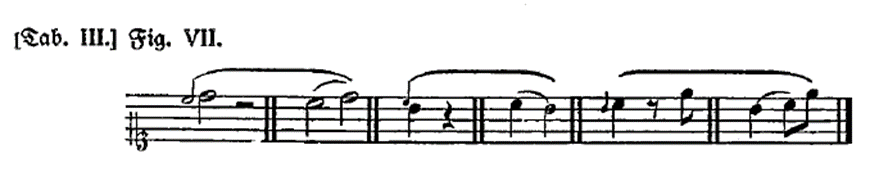

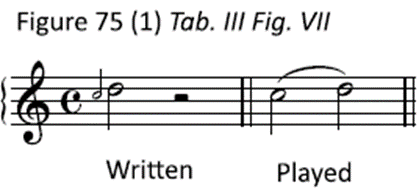

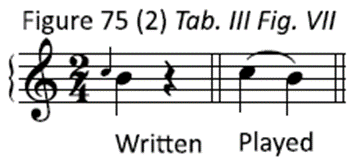

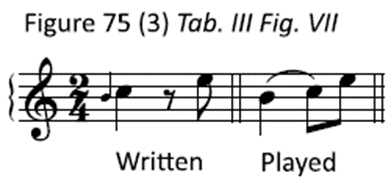

12) Figure 75 (Tab. III. Fig. VII) gives several examples of notation involving rests. C.P.E. notes that this notation is not the most correct and would be improved by using dotted or longer notes.

13) The short unchangeable appoggiatura

- These are always played quickly so that hardly any value is lost from the following tone

- They may have 1, 2 or 3 tails, all are played quickly

- In all cases the character of the principal notes remains unchanged

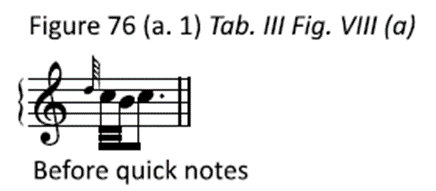

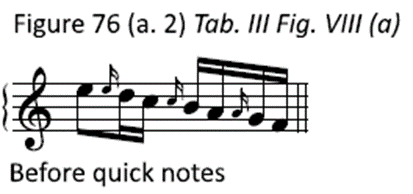

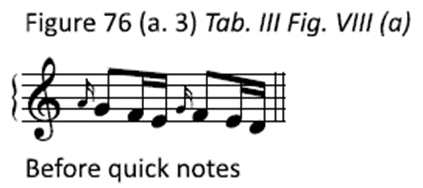

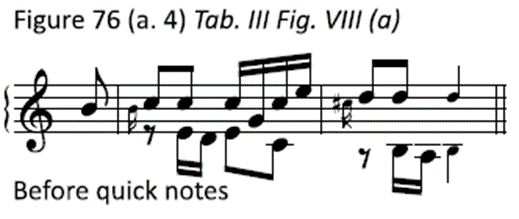

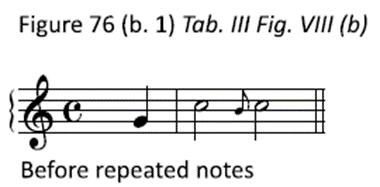

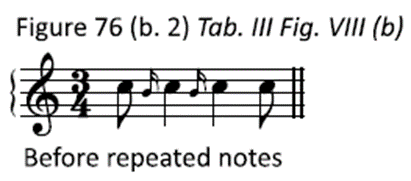

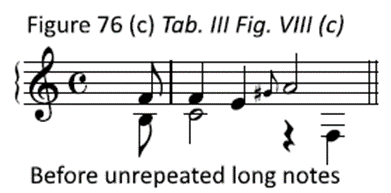

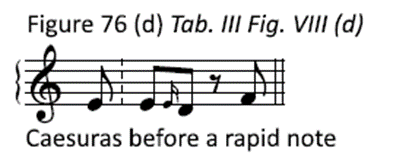

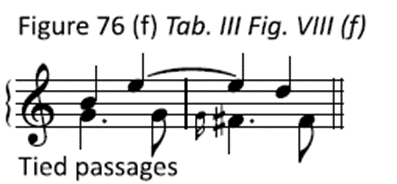

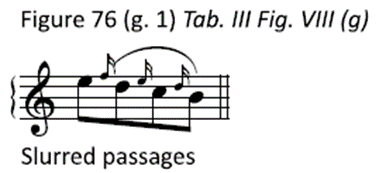

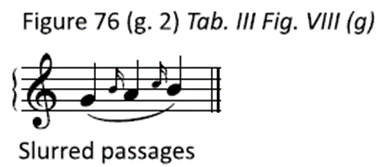

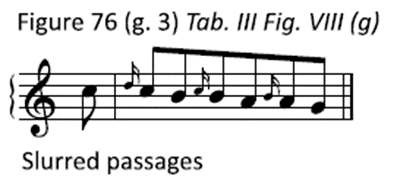

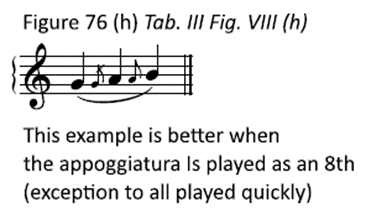

- Examples Figure 76 (Tab. III. Fig. VIII)

- Thay appear most frequently before quick notes

- Can appear before repeated notes

- Before unrepeated long notes

- Caesuras (Einschnitte) before a rapid note

- Syncopated passage

- Tied passages

- Slurred passages

- Example (h) is better when the appoggiatura Is played as an 8th (exception to all played quickly)

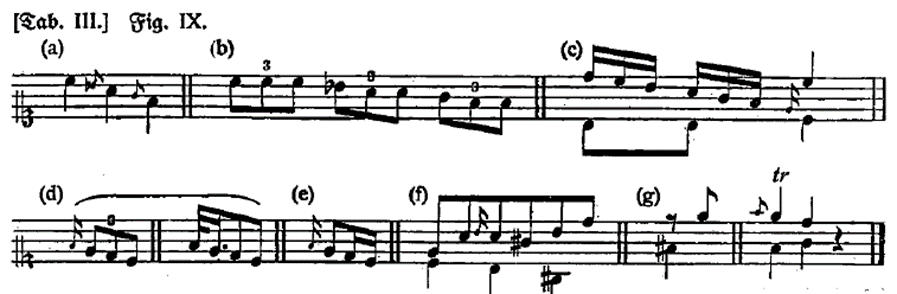

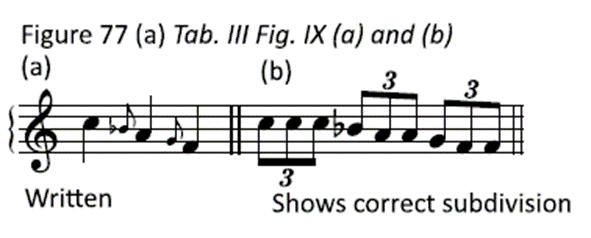

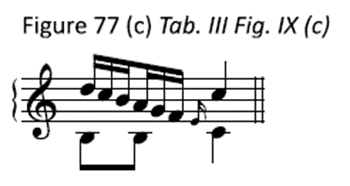

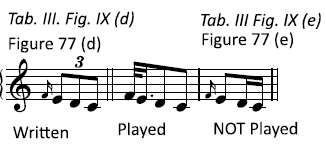

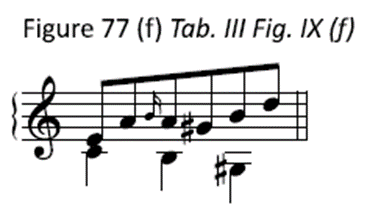

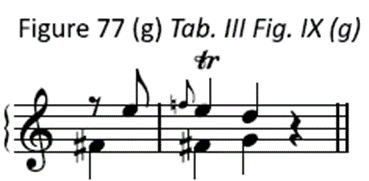

14) More examples of short appoggiaturas with explanations of various situations Figure 77 (Tab. III Fig. IX)

- (a) when they fill in an interval of a 3rd they are played quickly. But, if this is in an adagio tempo, play them slower, as an 8th to match the character (example b shows the correct division)

- (b) shows the correct division

- (c) the appoggiatura is the resolution of the triplet run, so it must be played quickly so the final melody note C does not lose much value

- (d) appoggiaturas before triplets must be played quickly so that the triplet rhythm remains clear

- (e) shows the appoggiatura in (d) incorrectly played (not a triplet rhythm)

- (f) when the appoggiatura forms an octave with the bass, it must be played quickly because of the emptiness of the octave interval

- (g) when the appoggiatura forms a diminished octave however, it is often played slower so as to prolong the tension

15) When a melody steps up and then returns to either the original tone or another appoggiatura, a short appoggiatura works well added to the middle tone.

- For all examples, legato is assumed, since detached notes should be performed more simply without ornamentation, and since an appoggiatura is joined with the following tone

- The speed should be moderte enough to make the ornaments playable and hearable

- Example (a) also shows that a long appoggiatura can be used

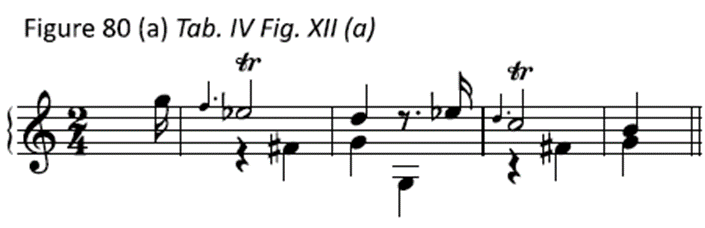

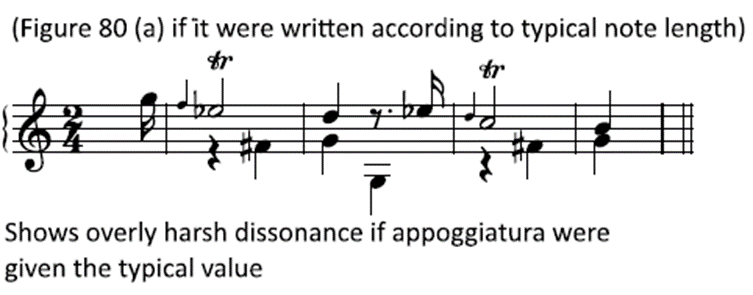

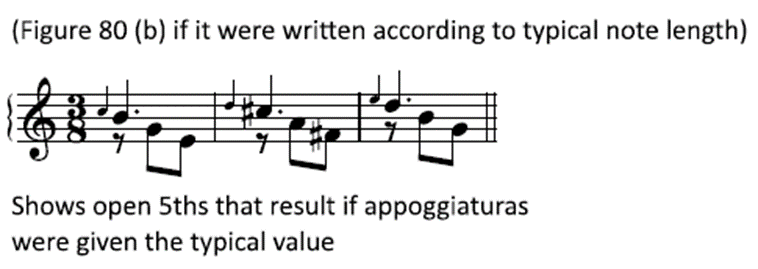

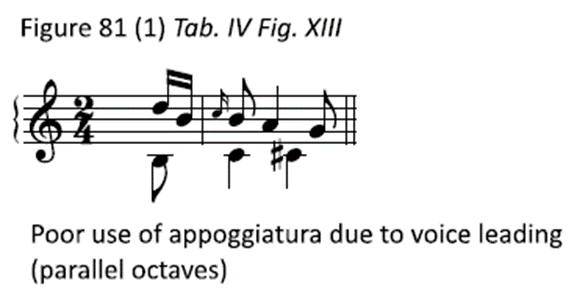

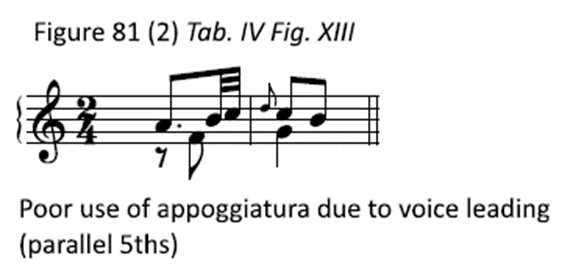

16) Adjust the length of the appoggiatura if needed to achieve the correct affect and avoid poor voice leading.

- An appoggiatura may take up more than half the value of the following tone

- Here the accompaniment determines the length. If the appoggiaturas are played as full quarter notes here, the fifths struck against the bass will sound ugly.

- If the appoggiatura is held beyond its written length here, it will create open 5ths

- Here the appoggiatura must not be held too long or the seventh will sound too harsh.

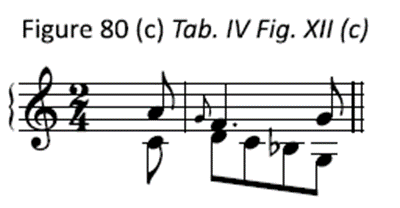

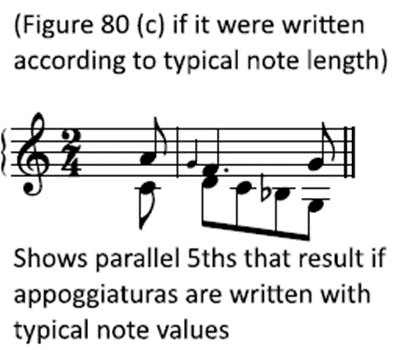

17) Correct voice leading must take precedence! The addition of an appoggiatura or any ornament must not disrupt the voice leading. Following are several examples of BAD ways to add appoggiaturas.

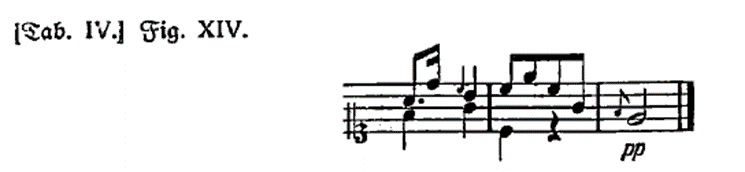

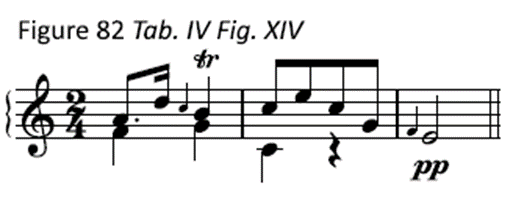

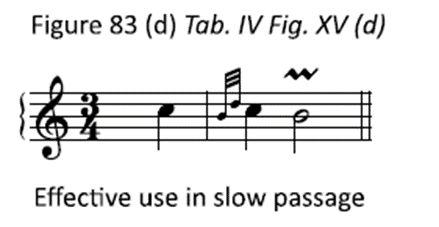

18) Using many appoggiaturas is often very effective in affectuoso passages since the releases of the appoggiaturas most often end pp.

However, in other cases using too many appoggiaturas without adding other ornaments or ornamenting the appoggiatura itself could make a melody bland.

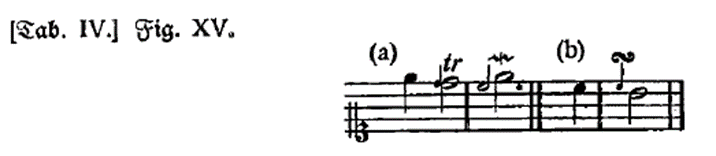

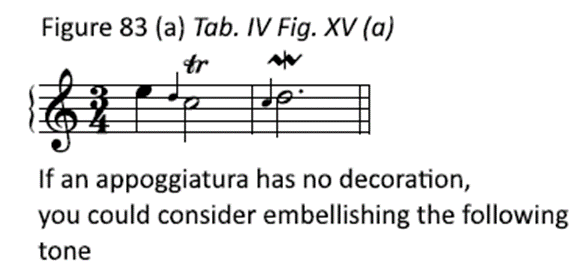

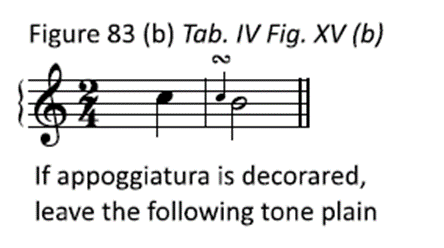

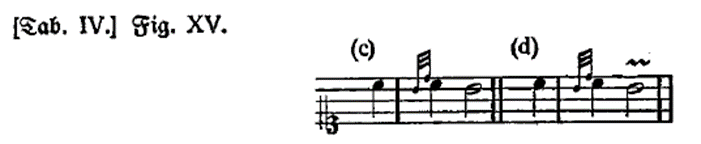

19) If the appoggiatura is left plain, an ornament on the following note might work well (a). If the appoggiatura is decorated, the following tone is best left plain (b).

20)

If the following note of an appoggiatura is to be decorated, it would be a good idea to write the appoggiatura in regular notation with its length clearly shown.

In slow pieces both the appoggiatura and following note might be embellished.

21) However, appoggiaturas and their following tones are often written in large notation to indicate to the performer that neither is to be embellished.

22) Placement of ornaments added to appoggiaturas and following tones:

- The note following an appoggiatura does not lose any of its own embellishments

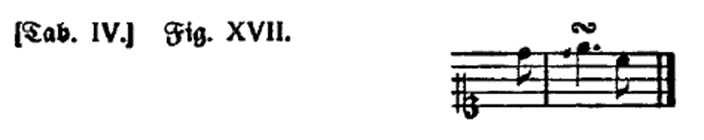

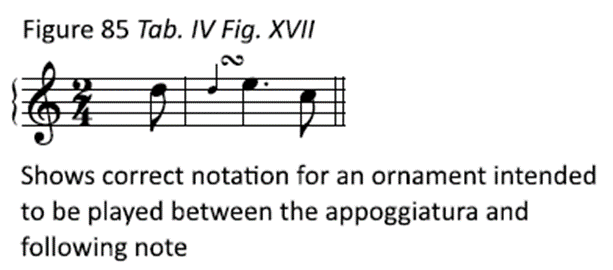

- Embellishments that belong to the appoggiatura should not be written over the following note. Place them directly over the appoggiatura, or between the appoggiatura and following note if they are to be performed between the two.

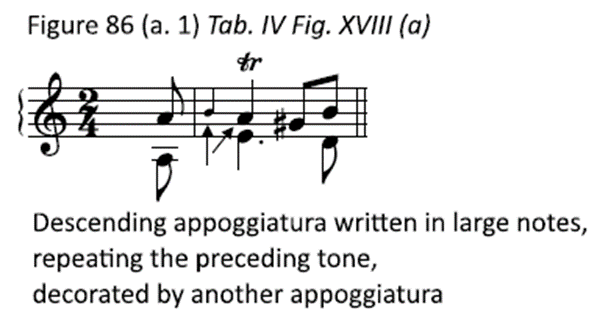

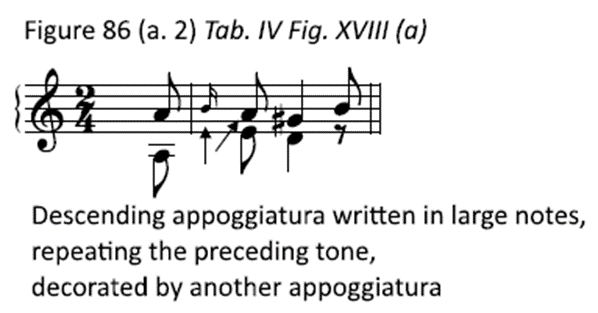

23)

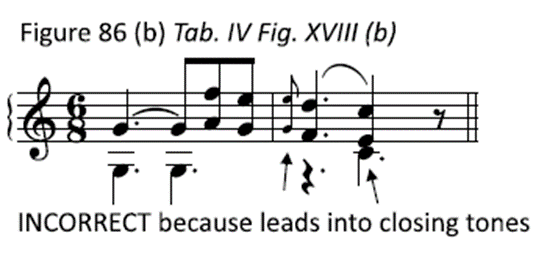

Descending appoggiaturas written in large notes, when they repeat the preceding tone may be decorated by another appoggiatura, long or short

These also may be decorated if they do not lead into closing tones. Example 86 (b) (Tab. IV Fig. XVIII (b)) shows an incorrect use because the appoggiaturas lead into closing tones.

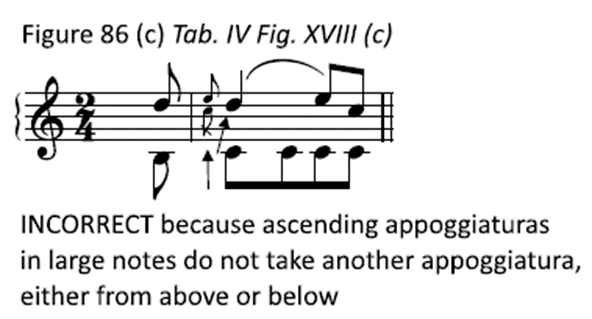

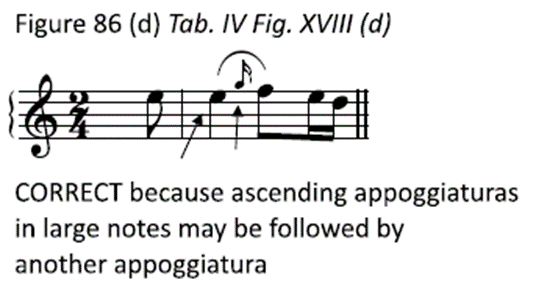

Ascending appoggiaturas in large notes do not take another appoggiatura, either from above or below

However, they may be followed by one

24) A few additional incorrect uses of the appoggiatura:

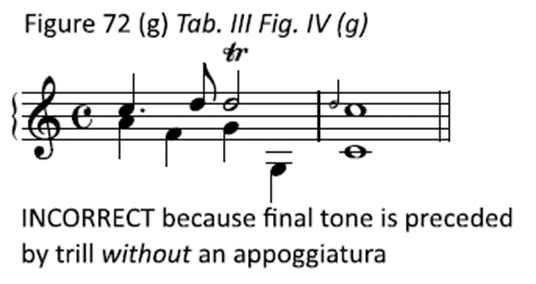

- It is wrong to place an appoggiatura before the final tone of a cadence when the final tone is preceded by a trill without an appoggiatura

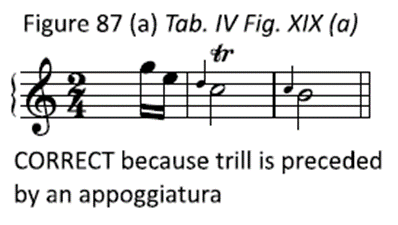

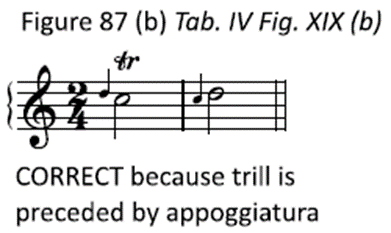

- However, a trill which has an appoggiatura before it may be followed by a final tone with appoggiatura, whether the final tone is lower or higher than the final trill.

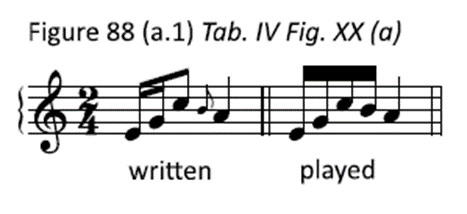

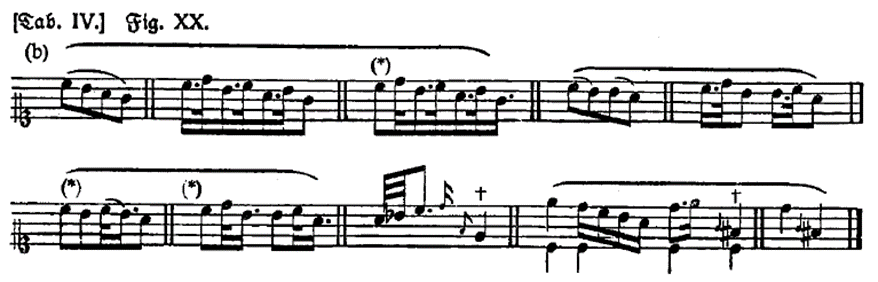

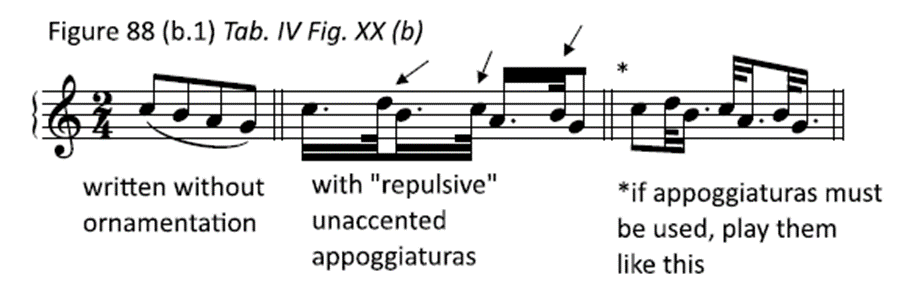

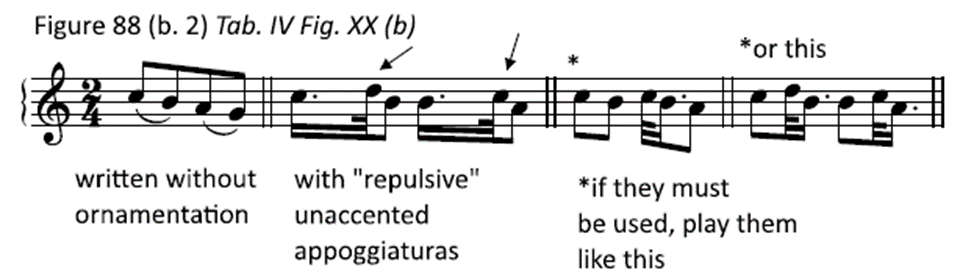

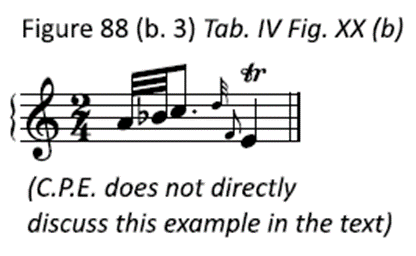

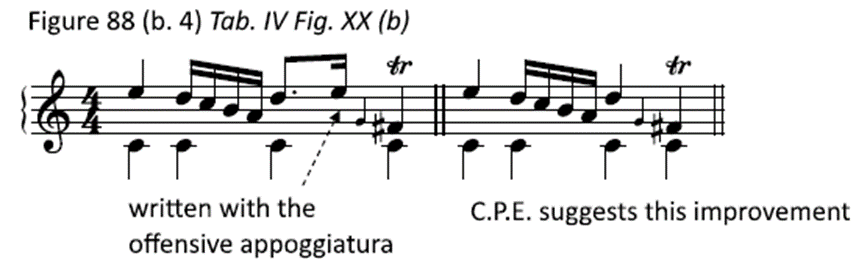

- Appoggiaturas should not take value from the notes before the tone. Figure 88 shows two examples of ways this could happen in performance.

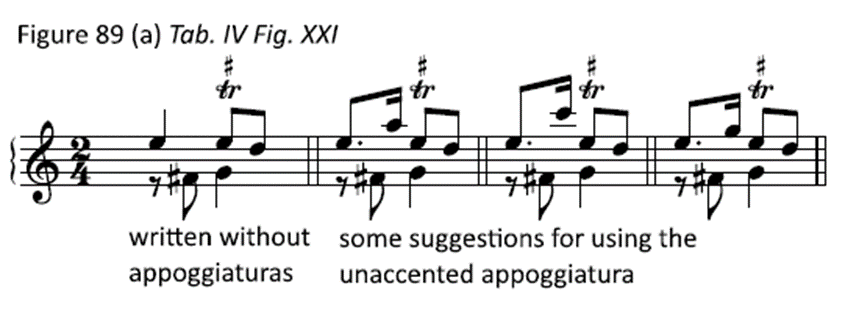

25) Unaccented appoggiaturas—C.P.E. hates them, but admits they are a popular thing. He suggests that if they must be used, one should shift them ahead to the next accent.

This is an example of differing advice from original sources. Unaccented appoggiaturas clearly did exist and have a place in the music of the time. J.J. Quantz discusses them in his treatise On Playing the Flute (1752, German and French editions), a classic text of instruction on Baroque music instruction.

Figure 89, example (a) (Tab. IV Fig. XXI) shows a good use of the unaccented appoggiatura, although the last bar is more fashionable than harmonious

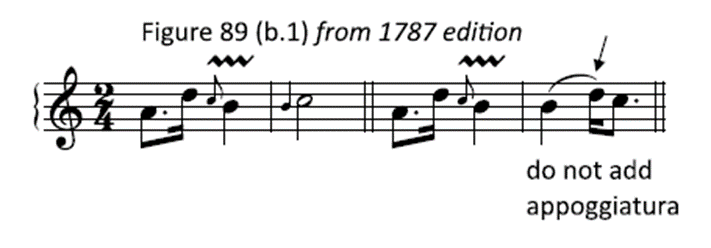

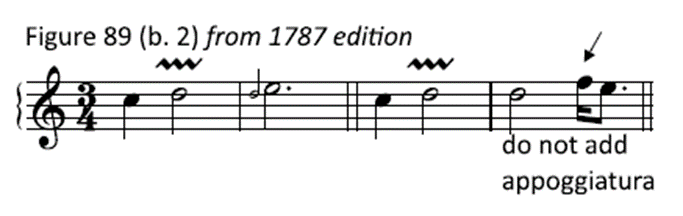

Figure 89 (b) (from 1787 edition) examples are to be avoided.

Figure 89 (b.1): THE PROBLEM is that a very short descending appoggiatura is inserted between an ascending one and its principal tone at a cadence. Do not do it!

Figure 89 (b.2): THE PROBLEM is that an appoggiatura is used in a melody which does not descend immediately afterward. Do not do it!

26) Other embellishments which are written as small notes will be explained in later sections.

SOURCES

Bach, C.P.E. Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments. Translated and edited by William J. Mitchell, W.W. Norton & Company, 1949, pp. 87-99.

Bach, Karl Philipp Emanuel. Versuch über die wahre Art das Klavier zu spielen. Edited by Walter Niemann, C.P. Khant, Leipzig, 1925, pp. 31-40.

CLICK HERE to download a pdf version of this study guide